There are many members of the "Greatest Generation" who never returned from fighting World War II. My generation, the baby boomers knew of World War II only through the stories our parents would share with us, through books and magazines which we read, and at through movies.

We were the lucky one's without even knowing it, but our parents knew that they were lucky.

We were fortunate for many reasons. Growing up in a prosperous, safe, and free nation seems an obvious reason to count one's blessings, but most fundamentally we were fortunate because our fathers lived to return from WWII, settled down, and marry our mothers.

That is the story of how so many of our families began.

When we baby boomers were small, and if we were lucky, we would listen to the stories of the Great Depression, and of World War Two (WWII) which our parents would occassionally share.

This article is a tribute to one member of the greatest generation, a hero from Central Illinois - one who never made it home to marry, or raise any children - a hero none the less. I can't honestly share his story, but I will at least introduce to you what I have learned of his story.

In Springfield, Illinois, and surrounding communities most have heard of the Kerasotes family. Every theater in town is a Kerasotes owned theater. Whatever people may feel about the lack of competition in local theater owership I'm not certain, but I suspect most feel a certain touch of pride at knowing that the Kerasotes family started their operations right here in Springfield, Illinois.

And so it is with a sense of civic pride that I want to share with the greater community another achievement of the Kerasotes family - a contribution which their family made to secure liberty for the United States, and the world.

Before I wrote this article I had never heard of Doctor Anthony "Gus" Kerasotes. I had not known that he had given his life upon the rough, and fridged seas of the North Atlantic in defense of his nation.

It was quite by chance that I came upon Anthony Kerasotes' tombstone which is located at Oak Ridge Cemetary. His stone isn't alone, for it is the centerpiece of the George G. Kerasotes' family burial plot.

Anthony Kerasotes was the son of Flora Beth Staikos Kerasotes, and Gus Kerasotes. He was the brother of George G., and John Kerasotes.

By the early 1940s Gus Kerasotes was operating over a dozen theaters in Central Illinois. He enlisted his children to assist him in the operation of the theaters.

Gus' son, George "Gus" Kerasotes shared in management responsibilities with his brothers. In 1947 George G. was married to Majorie Marie Rouke.

The Kerasotes theater chain continued to grow throughout the Midwest during the 1950s, and 1960s.

George G. Kerasotes ended his relationship with Kerasotes Theaters in 1985, and founded the George Kerasotes Chain. GKC Theaters was based in Springfield, Illinois.

After George G. Kerasotes died in March of 2001 his daughter Beth Kerasotes took over as the head of GKC Theaters.

On May 18, 2005 GKC Theaters was sold to Carmike Cinemas. Based in Columbus, Georgia Carmike acquired GKC Theaters for $66 million dollars. The remaining Kerasotes theaters are operated by George Kerasotes' brothers, and their families.

Photo: Anthony Kerasotes Tombstone

An entry appears upon Anthony Kerasotes' tombstone (see photo above) which refers to how Anthony Kerasotes gave his life while serving aboard the U.S.S. Leary during World War Two. What was the story behind his sacrafice?

As I stood before his tombstone, under a warm July sun, that Anthony Kerasotes had died on Christmas day in 1943 in the freezing cold waters of the North Atlantic. I know from personal experience that it is especially tragic to lose a family member during the Christmas season. Certainly his sacrafice, the loss of this son must have had a profound effect upon his family.

Anthony Kerasotes had attended the University of Illinois at Urbana, earning a degree in medicine, and when his country was in need, the young Doctor Kerasotes met that challenge through his naval service.

Anthony Kerasotes served aboard a WWI era "Four Stack" destroyer. A destroyer which had been designated for anti-submarine patrol, and escort duty.

On September 23, 2000 Anthony Karasotes was posthumously awarded the Navy, and Marine Corps Medal for his Heroism for on 24 Dec. 1943. By his initiative, courageous actions, and complete dedication to duty, Lt. Kerasotes reflected great credit upon himself and upheld the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service.

Photo: U.S.S Leary. Torpedoed and sunk by U-275 North of the Azores December 24 1943

The University of Illinois Alumni Association has an entry for Anthony Kerasotes posted by his cousin. I've included it below.

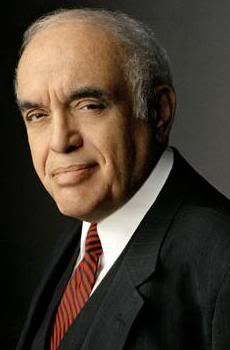

Photo: Anthony Kerasotes

Graduation Year University of Illinois: 1934

Service branch: Navy

Rank: Lieutenant (JG)

Date of Birth: 1912

Date of Death: 12/24/1943

Membership: AMA

The President of the United States takes pride in presenting the NAVY AND MARINE CORPS MEDAL posthumously to Lt. (JG) Anthony Kerasotes, for heroism in connection with operations against the German Navy while serving as Doctor aboard USS LEARY in the North Atlantic Ocean on 24 Dec. 1943. While engaged in anti-submarine operations, LEARY was struck by a torpedo and heavily damaged. Lt. Kerasotes immediately initiated medical procedures on the scores of wounded personnel. When the word was passed to abandon ship, he helped ensure the injured were transported over the side. When the final, fatal torpedo struck LEARY, he was continuing his medical attention to the injured and was one of the last personnel to enter the water. While in the cold water, he helped ensure the men were all taken care of and continued to swim between groups encouraging and assisting them until he himself drowned. By his initiative, courageous actions, and complete dedication to duty, Lt. Kerasotes reflected great credit upon himself and upheld the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service.

Submitted to U of I Alumni Association by Steve Kerasotes, cousin.

Here's the incredible story of the tragic sinking of the Leary by Lt. Scott Robinson, H Division, USS North Carolina Historical Detachment:

On 17 December, 1943, CTG 21.14 commanded by Captain A.J. Isbell aboard the USS Card (CVE-11), left Casablanca and steamed in support of convoy GUS-24. Orders from Washington detached the Card group, Leary (DD158), Schenck (DD159), Decatur and Babbitt, to track down a U-boat concentration around latitude 45N, longitude 22W. The Card was one of the "jeep" (escort) carriers and the destroyers were old WWI vintage four-stack destroyers.

Just before dusk on the 23rd, the seas were so rough that a Wildcat and her crew were lost from the deck of the Card. An additional sailor was swept off her flight deck. While the air crew was recovered, the sailor was nowhere to be found in the rough seas. Decatur's steering gear room was flooded and she was being steered by hand.

Capt. Isbell had no way of knowing that group Borkum (13 subs) had rallied and lay in waiting for their prey 85 miles dead ahead. With the rough seas and the stricken Decatur, Isbell could not evade the group and decided to press ahead. The die was cast.

At 2200, U-305 sighted Card and ordered the wolfpack to close. At 2230 Card's radar picked up her first surface contact. Soon, there were too many to track. Card, with Decatur in close proximity had to make best speed dead ahead to outrun the wolfpack.

Leary and the stricken Decatur followed the Card and took evasive action.

Things began to happen in rapid succession. The heat was on and the ships were in the middle of a cauldron of war and mother nature's fury.

Several subs pursued Card through the night. At 0630, she was able to launch her first aircraft and a sub was immediately spotted 7000 yards on her port quarter. The subs dove under the safety of the waves and Card was spared.

Meanwhile, the two destroyers, Schenck and Leary were engaged in battle with the remainder of Group Borkum.

Torpedoes were seen in the water heading for Schenck. The closest was one that went right under her bow. A wave had crested just in time and the Schenck was spared. She steamed towards Leary to join in a systematic search of the region.

As Leary moved out to chase the more distant, Schenck made a 4th contact and lost it at about 2500 yards. She sighted a U-boat diving and evaded a torpedo to port. She closed to 800 yards and at 0145, began a nine depth charge pattern. The U-boat was damaged and surfaced at 0215. Schenck closed for the coup-de-gras. The boat dove. At 0229, secondary underwater explosions were heard and a brief surface contact was made. A distress signal was intercepted. As Schenck closed on the stricken U-boat, she slipped under the waves with no survivors. An oil slick surfaced. This was the end of U-645. The U-boat sank with 55 men and group Borkum's Doctor.

A series of mishaps were rapidly occurring aboard Leary. At 0158, Leary commanded by Commander James Kyes, made radar contact and fired a star shell to illuminate the target. This only illuminated her own position for the shadowing subs. As the sub submerged to periscope depth, there was a misunderstanding and Leary's guns continued to fire. At 0208, when sound contact was gained, the squawk box between the sound room and bridge failed to function and almost two minutes elapsed before Commander Kyes got the word, and, too late, ordered right rudder.

U-275 had been watching Leary for almost ten minutes. At 0210 as Leary commenced her turn, Oberluetnant Bork fired two well aimed Zaukoning torpedoes. They hit Leary in rapid succession. One in the after engine room, and one in the after hold. All power was lost. The crew in the engineering spaces were killed outright by severed steam lines. She listed to starboard by 25 degrees and settled rapidly. The torpedo men barely had time to safe her depth charges. This action undoubtedly saved many lives. The entire aft section of the destroyer became a tangle of twisted metal and human lives extinguished. Leary began to break apart and settle. RT Butch Hauer started the auxiliary generator and called to Schenck for assistance. As Schenck was taking an oil sample, Leary five miles distant, had reported that she had just been torpedoed. U-275 's fish had hit their mark. Schenck headed at flank speed to aid her sister.

Three or four minutes after the explosions, the XO, Lt. Robert Watson, concluded a quick inspection. He reported to Commander Kyes. Kyes ordered abandon ship. BM Walter Eshelman directed men to jettison all floatable gear and abandonment was professional and orderly as if a drill. Watson reported that everyone except himself and the skipper had left and obtained permission for one more look around to see if any wounded men had been forgotten. U-382 had moved into position and launched a third torpedo. It struck at 0241 in the forward engine space. Leary broke apart and went down fast. Commander Kyes ordered Watson and Hauer over the side and handed his life jacket to a black mess attendant who had none. Commander Kyes was never seen again.

As the ship slipped beneath the waves, her bow rose high in the air. The steam escaping form the spaces and the constant blowing of her distress horn made an eerie, haunting sound. Men swam away from her as fast as they could, dragging the injured and weak behind them. They had to escape the suction of the ship, and any secondary explosions from unsafed depth charges.

Over 60 men were killed instantly by the explosions, and about 100 were now in the 43 degree water.

As Schenck arrived on the scene, she could not pick up survivors. The water was infested with Group Borkum. A rain squall developed and pounded the waters. In a bold move, Cmdr. Logsdon slowed Schenck and dropped her gig in the water with four men aboard. He gave the order to a young Lieutenant (jg), "Save as many as you can. I don't know when we'll be back. Good luck and may God be with you." With that, the gig was in the water among the survivors. Schenck pressed on to chase Borkum out of the area.

In the water, there was no officer, no enlisted man, no black, no white. They were all sailors fighting to stay alive. Afraid that, at any moment, a U-boat would surface and machinegun them all. Not only were they fighting the enemy, they were now fighting the cruel sea. One by one, they slowly succumbed to their injuries and slipped beneath the waves. The strong fought to hold on to the wounded, but their hands and arms ceased to function.

Four hours later, when day broke on Christmas Eve, Schenck returned to the site. She slowly steamed among the debris and bodies. Her crew tried to identify the dead from the names stenciled on their clothing. She pulled 59 hypothermic and injured men from the water. 97 United States sailors perished on Christmas Eve of 1943 in the icy North Atlantic.

To learn more about the Four Stacker ships, and the men that manned them please visit this great site!

http://www.kennand.com/kenna/Four_Stacker/

Sources:http://www.illinoistimes.com/gbase/Gyrosite/Content

http://www.legis.state.il.us/legislation/legisnet92/srgroups/PDF/920SR0080.pdf